This essay contains outdated language which may be considered offensive. Originally published 1925

Part 2:

That laughter for which we are so justly famed has had in late years its over-tones of pain. Now for some time past it has been used by colored men who have gained a precarious footing on the stage to conceal the very real dolor raging in their breasts. To be by force of circumstances the most dramatic figure in a country; to be possessed of the wells of feeling, of the most spontaneous instinct for effective action and to be shunted no less always into the rôle of the ridiculous and funny,—that is enough to create the quality of bitterness for which we are ever so often rebuked. Yet that same laughter influenced by these same untoward obstacles has within the last four years known a deflection into another channel, still productive of mirth, but even more than that of a sort of cosmic gladness, the joy which arises spontaneously in the spectator as a result of the sight of its no less spontaneous bubbling in others. What hurt most in the spectacle of the Bert Williams’ funny man and his forerunners was the fact that the laughter which he created must be objective. But the new “funny man” among black comedians is essentially funny himself. He is joy and mischief and rich, homely native humor personified. He radiates good feeling and happiness; it is with him now a state of being purely subjective. The spectator is infected with his high spirits and his excessive good will; a stream of well-being is projected across the footlights into the consciousness of the beholder.

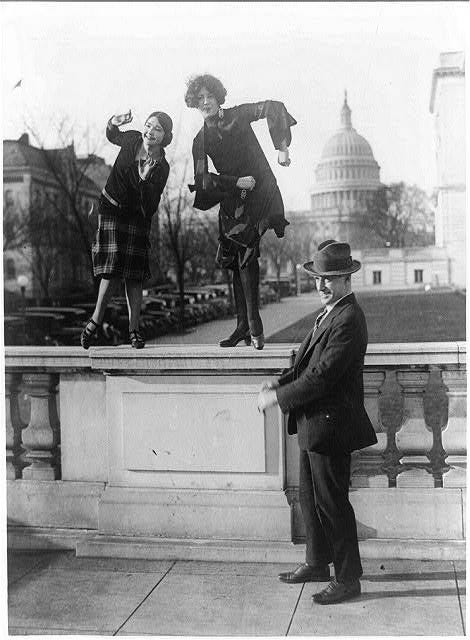

This phenomenon has been especially visible in the rendition of the colored musical “shows,” Shuffle Along, Runnin’ Wild, Liza, which livened up Broadway recently for a too brief season. Those of us who were lucky enough to compare with the usual banality of musical comedy, the verve and pep, the liveliness and gayety of those productions will not soon forget them. The medley of shades, the rich colorings, the abundance of fun and spirits on the part of the players all combined to produce an atmosphere which was actually palpable, so full was it of the ecstasy and joy of living. The singing was inimitable; the work of the chorus apparently spontaneous and unstudied. Emotionally they garnished their threadbare plots and comedy tricks with the genius of a new comic art.

The performers in all three of these productions gave out an impression of sheer happiness in living such as I have never before seen on any stage except in a riotous farce which I once saw in Vienna and where the same effect of superabundant vitality was induced. It is this quality of vivid and untheatrical portrayal of sheer emotion which seems likely to be the Negro’s chief contribution to the stage. A comedy made up of such ingredients as the music of Sissle and Blake, the quaint, irresistible humor of Miller and Lyles, the quintessence of jazzdom in the Charleston, the superlativeness of Miss Mills’ happy abandon could know no equal. It would be the line by which all other comedy would have to be measured. Behind the banalities and clap-trap and crudities of these shows, this supervitality and joyousness glow from time to time in a given step or gesture or in the teasing assurance of such a line as: “If you’ve never been vamped by a brown-skin, you’ve never been vamped at all.”

And as Carl van Vechten recently in his brilliant article, Prescription for the Negro Theater, so pointedly advises and prophesies, once this spirit breaks through the silly “childish adjuncts of the minstrel tradition” and drops the unworthy formula of unoriginal imitation of the stock revues, there will be released on the American stage a spirit of comedy such as has been rarely known.

• • • • •

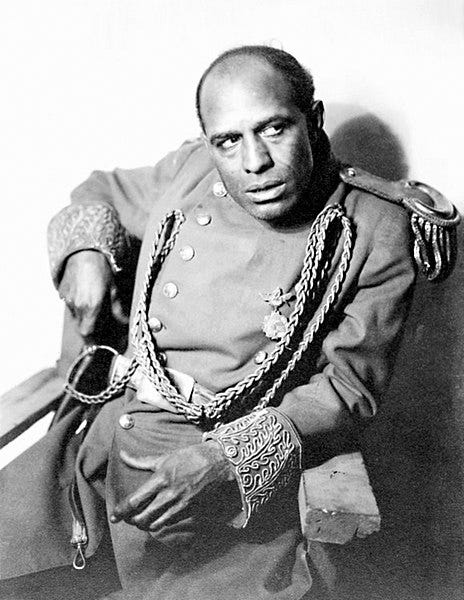

The remarkable thing about this gift of ours is that it has its rise, I am convinced, in the very woes which beset us. Just as a person driven by great sorrow may finally go into an orgy of laughter, just so an oppressed and too hard driven people breaks over into compensating laughter and merriment. It is our emotional salvation. There would be no point in mentioning this rather obvious fact were it not that it argues also the possession on our part of a histrionic endowment for the portrayal of tragedy. Not without reason has tradition made comedy and tragedy sisters and twins, the capacity for one argues the capacity for the other. It is not surprising then that the period that sees the Negro actor on the verge of great comedy has seen him breaking through to the portrayal of serious and legitimate drama. No one who has seen Gilpin and Robeson in the portrayal of The Emperor Jones and of All God’s Chillun can fail to realize that tragedy, too, is a vastly fitting rôle for the Negro actor. And so with the culminating of his dramatic genius, the Negro actor must come finally through the very versatility of his art to the universal rôle and the main tradition of drama, as an artist first and only secondarily as a Negro.

• • • • •

Nor when within the next few years, this question comes up,—as I suspect it must come up with increasing insistence, will the more obvious barriers seem as obvious as they now appear. For in this American group of the descendants of Mother Africa, the question of color raises no insuperable barrier, seeing that with chameleon adaptability we are able to offer white colored men and women for Hamlet, The Doll’s House and the Second Mrs. Tanqueray; brown men for Othello; yellow girls for Madam Butterfly; black men for The Emperor Jones. And underneath and permeating all this bewildering array of shades and tints is the unshakable precision of an instinctive and spontaneous emotional art.

All this beyond any doubt will be the reward of the “gift of laughter” which many black actors on the American stage have proffered. Through laughter we have conquered even the lot of the jester and the clown. The parable of the one talent still holds good and because we have used the little which in those early painful days was our only approach we find ourselves slowly but surely moving toward that most glittering of all goals, the freedom of the American stage. I hope that Hogan realizes this and Cole and Walker, too, and that lastly Bert Williams the inimitable, will clap us on with those tragic black-gloved hands of his now that the gift of his laughter is no longer tainted with the salt of chagrin and tears.

![a black and white photo of the full cast of 'Shuffle Along' with the caption Caption: Miller & Lyles [...] Sissle & Blake and their All-Around the world company in their ...... Musical knock-out. "Shuffle Along" now playing at the Selwyn Theatre ..... Boston.' a black and white photo of the full cast of 'Shuffle Along' with the caption Caption: Miller & Lyles [...] Sissle & Blake and their All-Around the world company in their ...... Musical knock-out. "Shuffle Along" now playing at the Selwyn Theatre ..... Boston.'](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!R-CB!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcaf4a82d-2d64-47f4-8ab9-e05811b35d70_1456x1148.webp)