This essay contains outdated language which may be considered offensive. Originally published 1925

Part 1:

THE black man bringing gifts, and particularly the gift of laughter, to the American stage is easily the most anomalous, the most inscrutable figure of the century. All about him and within himself stalks the conviction that like the Irish, the Russian and the Magyar he has some peculiar offering which shall contain the very essence of the drama. Yet the medium through which this unique and intensely dramatic gift might be offered has been so befogged and misted by popular preconception that the great gift, though divined, is as yet not clearly seen.

Popular preconception in this instance refers to the pressure of white opinion by which the American Negro is surrounded and by which his true character is almost submerged. For years the Caucasian in America has persisted in dragging to the limelight merely one aspect of Negro characteristics, by which the whole race has been glimpsed, through which it has been judged. The colored man who finally succeeds in impressing any considerable number of whites with the truth that he does not conform to these measurements is regarded as the striking exception proving an unshakable rule. The medium then through which the black actor has been presented to the world has been that of the “funny man” of America. Ever since those far-off times directly after the Civil War when white men and colored men too, blacking their faces, presented the antics of plantation hands under the caption of “Georgia Minstrels” and the like, the edict has gone forth that the black man on the stage must be an end-man.

In passing one pauses to wonder if this picture of the black American as a living comic supplement has not been painted in order to camouflage the real feeling and knowledge of his white compatriot. Certainly the plight of the slaves under even the mildest of masters could never have been one to awaken laughter. And no genuinely thinking person, no really astute observer, looking at the Negro in modern American life, could find his condition even now a first aid to laughter. That condition may be variously deemed hopeless, remarkable, admirable, inspiring, depressing; it can never be dubbed merely amusing.

• • • • •

It was the colored actor who gave the first impetus away from this buffoonery. The task was not an easy one. For years the Negro was no great frequenter of the theater. And no matter how keenly he felt the insincerity in the presentation of his kind, no matter how ridiculous and palpable a caricature such a presentation might be, the Negro auditor with the helplessness of the minority was powerless to demand something better and truer. Artist and audience alike were in the grip of the minstrel formula. It was at this point in the eighteen-nineties that Ernest Hogan, pioneer comedian of the better type, changed the tradition of the merely funny, rather silly “end-man” into a character with a definite plot in a rather loosely constructed but none the less well outlined story. The method was still humorous, but less broadly, less exclusively. A little of the hard luck of the Negro began to creep in. If he was a buffoon, he was a buffoon wearing his rue. A slight, very slight quality of the Harlequin began to attach to him. He was the clown making light of his troubles but he was a wounded, a sore-beset clown.

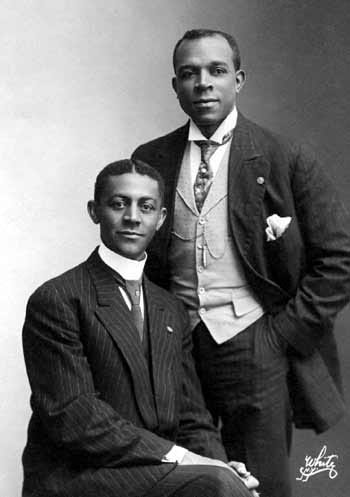

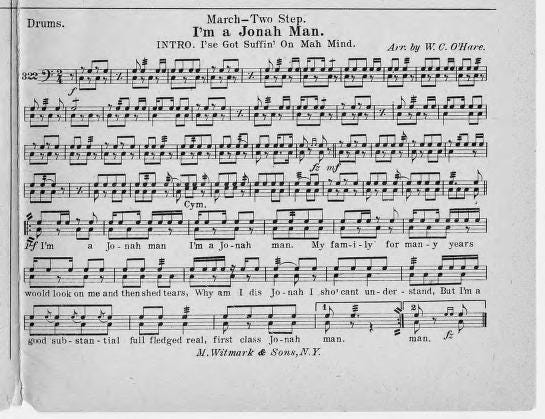

This figure became the prototype of the plays later presented by those two great characters, Williams and Walker. The ingredients of the comedies in which these two starred usually consisted of one dishonest, overbearing, flashily dressed character (Walker) and one kindly, rather simple, hard-luck personage (Williams). The interest of the piece hinged on the juxtaposition of these two men. Of course these plays, too, were served with a sauce of humor because the public, true to its carefully taught and rigidly held tradition, could not dream of a situation in which colored people were anything but merely funny. But the hardships and woes suffered by Williams, ridiculous as they were, introduced with the element of folk comedy some element of reality.

![an illustration of a country road running along a wood fence. Text box with black and white photographs appears in the bottom right corner. Inside the text box, there are two small circular black and white photographs of two African American men. Black type in box reads: [WHEN / THE MOON / SHINES / Introduced with pleasing effect in /WILLIAMS & WALKER'S / BIG PRODUCTION / WORDS BY / ALEX ROGERS / MUSIC BY / JAMES VAUGHAN / The ATTUCKS / MUSIC / PUBLISHING COMPANY / 1255 - 57 BROADWAY N.Y.]. Handwritten in ink, in the top left corner, is [Mrs. D.W. McDonald]. an illustration of a country road running along a wood fence. Text box with black and white photographs appears in the bottom right corner. Inside the text box, there are two small circular black and white photographs of two African American men. Black type in box reads: [WHEN / THE MOON / SHINES / Introduced with pleasing effect in /WILLIAMS & WALKER'S / BIG PRODUCTION / WORDS BY / ALEX ROGERS / MUSIC BY / JAMES VAUGHAN / The ATTUCKS / MUSIC / PUBLISHING COMPANY / 1255 - 57 BROADWAY N.Y.]. Handwritten in ink, in the top left corner, is [Mrs. D.W. McDonald].](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!eZTh!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Facb6f1b7-1de8-4904-b91b-4cf04a9e8fd1_800x1004.jpeg)

Side by side with Williams and Walker, who might be called the apostles of the “legitimate” on the stage for Negroes, came the merriment and laughter and high spirits of that incomparable pair, Cole and Johnson. But they were essentially the geniuses of musical comedy. At that time their singers and dancers outsang and outdanced the neophytes of contemporary white musical comedies even as their followers to this day out- sing and outdance in their occasional appearances on Broadway their modern neighbors. Just what might have been the ultimate trend of the ambition of this partnership, the untimely death of Mr. Cole rendered uncertain; but speaking offhand I should say that the relation of their musical comedy idea to the fixed plot and defined dramatic concept of the Williams and Walker plays molded the form of the Negro musical show which still persists and thrives on the contemporary stage. It was they who capitalized the infectious charm of so much rich dark beauty, the verve and abandon of Negro dancers, the glorious fullness of Negro voices. And they produced those effects in the Red Shawl in a manner still unexcelled, except in the matter of setting, by any latter-day companies.

But Williams and Walker, no matter how dimly, were seeking a method whereby the colored man might enter the “legitimate.” They were to do nothing but pave the way. Even this task was difficult but they performed it well.

• • • • •

Those who knew Bert Williams say that his earliest leanings were toward the stage; but that he recognized at an equally early age that his color would probably keep him from ever making the “legitimate.” Consequently, deliberately, as one who desiring to become a great painter but lacking the means for travel and study might take up commercial art, he turned his attention to minstrelsy. Natively he possessed the art of mimicry; intuitively he realized that his first path to the stage must lie along the old recognized lines of “funny man.” He was, as few of us recall, a Jamaican by birth; the ways of the American Negro were utterly alien to him and did not come spontaneously; he set himself therefore to obtaining a knowledge of them. For choice he selected, perhaps by way of contrast, the melancholy out-of-luck Negro, shiftless, doleful, “easy”; the kind that tempts the world to lay its hand none too lightly upon him. The pursuit took him years, but at length he was able to portray for us not only that “typical Negro” which the white world thinks is universal but also the special types of given districts and localities with their own peculiar foibles of walk and speech and jargon. He went to London and studied under Pietro, greatest pantomimist of his day, until finally he, too, became a recognized master in the field of comic art.

But does anyone who realizes that the foibles of the American Negro were painstakingly acquired by this artist, doubt that Williams might just as well have portrayed the Irishman, the Jew, the Englishman abroad, the Scotchman or any other of the vividly etched types which for one reason or another lend themselves so readily to caricature? Can anyone presume to say that a man who travelled north, east, south and west and even abroad in order to acquire accent and jargon, aspect and characteristic of a people to which he was bound by ties of blood but from whom he was natively separated by training and tradition, would not have been able to portray with equal effectiveness what, for lack of a better term, we must call universal rôles?

There is an unwritten law in America that though white may imitate black, black, even when superlatively capable, must never imitate white. In other words, grease-paint may be used to darken but never to lighten.

Williams’ color imposed its limitations upon him even in his chosen field. His expansion was always upward but never outward. He might portray black people along the gamut from roustabout to unctuous bishop. But he must never stray beyond those limits. How keenly he felt this few of us knew until after his death. But it was well known to his intimates and professional associates. W. C. Fields, himself an expert in the art of amusing, called him “the funniest man I ever saw and the saddest man I ever knew.”

He was sad with the sadness of hopeless frustration. The gift of laughter in his case had its source in a wounded heart and in bleeding sensibilities.